Date Published: May 3, 2025

By Olga Levitski

The Pioneers: Setting the Stage

When the first Russian ballet dancers began arriving in Toronto in the early 20th century, few could have predicted the profound impact they would have on the city's cultural landscape. Like delicate but determined snowflakes carried on winter winds from St. Petersburg, these artists brought with them not just technique and tradition, but a passion that would transform Toronto from a provincial outpost into one of North America's most vibrant ballet centers.

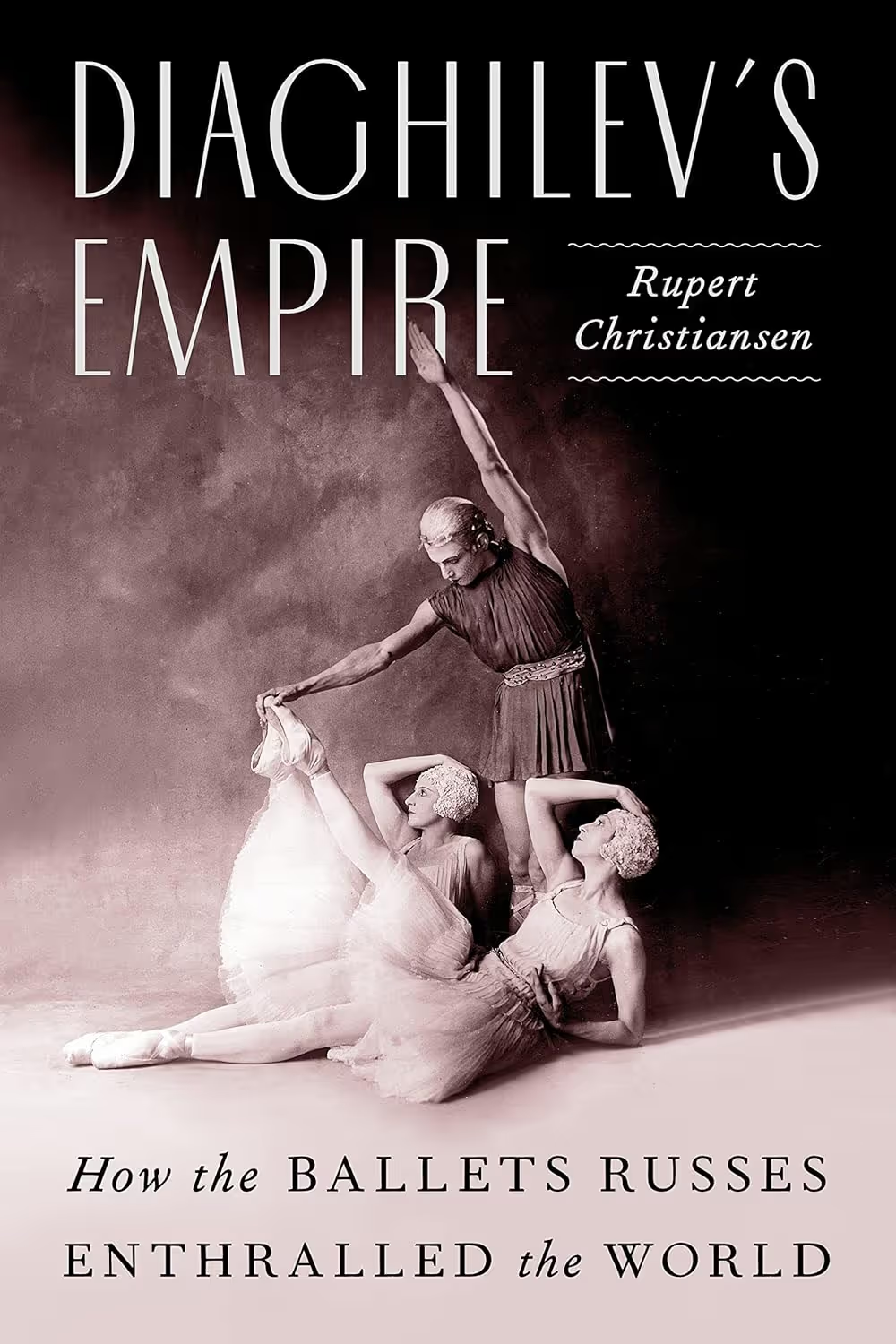

Toronto's first meaningful exposure to Russian ballet came not from immigrants but through touring companies. In 1921, when dancers from Diaghilev's Ballets Russes first performed at the Royal Alexandra Theatre, Torontonians were mesmerized by the distinctly Russian combination of technical precision and emotional expressiveness.

Local newspapers described audiences sitting in "stunned silence before erupting into thunderous applause." The city had never seen anything like it. As a Globe and Mail reporter declared, “Ballet fever has swept Toronto,” with admirers lining up for tickets a week in advance of the show and “showing the same enthusiasm for this delightful form of entertainment as [in] London and New York.”

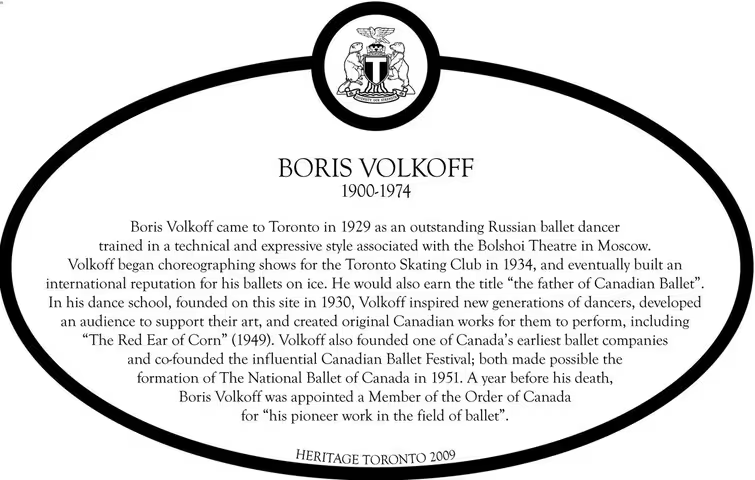

The economic turmoil following the Russian Revolution pushed many dancers westward, with some finding their way to Canada. Notably, Boris Volkoff—often called the "father of Canadian ballet"—arrived in Toronto in 1929 after dancing with the State Theater of Kyiv and briefly with Diaghilev's company. Despite Toronto's relatively undeveloped dance scene, Volkoff saw potential.

"Toronto has no ballet tradition," he reportedly said, "which means we can build one ourselves." And build he did. The Volkoff Canadian Ballet, founded in 1936, became Toronto's first permanent ballet company. Though small and operating on shoestring budgets, Volkoff's ensemble introduced Russian training methods and repertoire to Canadian dancers, laying groundwork for future generations.

The Cold War Era: Ballet as Cultural Diplomacy

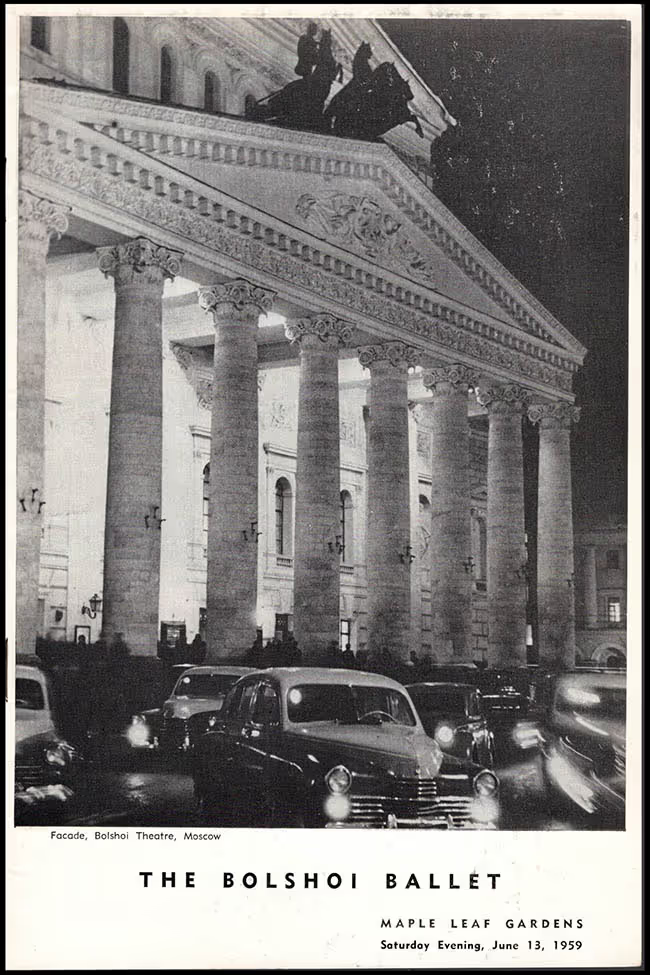

The post-World War II era marked a fascinating chapter in Toronto's Russian ballet story. While political tensions simmered between East and West, ballet became an unexpected form of cultural diplomacy. The Bolshoi Ballet's 1959 Canadian tour brought Soviet stars like Maya Plisetskaya to Toronto's Maple Leaf Gardens, where over 10,000 spectators gathered—the largest ballet audience in Canadian history at that time.

Toronto Star critic Nathan Cohen wrote: "Political differences were forgotten as the final curtain fell. The standing ovation lasted seventeen minutes by my watch, with cries of 'Bravo!' in English mingling with 'Molodets!' in Russian from immigrant attendees."

This period also saw an influx of Soviet-trained dancers who defected or emigrated to the West. Sergei Sawchyn, who escaped from the USSR via Austria in 1951, established one of Toronto's first Russian ballet schools in a converted warehouse near Dundas and Spadina. His studio became a hub for Toronto's growing Eastern European community, with Saturday classes conducted entirely in Russian and Ukrainian.

The National Ballet of Canada, founded in 1951, actively recruited Russian-trained dancers and teachers. Founder Celia Franca recognized that Russian pedagogical methods provided systematic training that produced exceptional dancers. By the 1960s, nearly half of the company's principal dancers had studied under Russian émigré teachers, either in Toronto or elsewhere in Canada.

The Nureyev Effect: Raising the Barre

No discussion of Russian ballet's influence on Toronto would be complete without mentioning Rudolf Nureyev. Though not permanently based in the city, his frequent collaborations with the National Ballet of Canada in the 1970s and 1980s revolutionized the company and, by extension, Toronto's ballet scene.

Nureyev's 1972 production of "The Sleeping Beauty" for the National Ballet elevated the company to international prominence. His demands for excellence pushed dancers to new technical heights, while his celebrity status attracted unprecedented audience interest. Karen Kain, who became Nureyev's frequent partner, recalled: "He expected perfection and wouldn't accept anything less. He changed how we thought about ourselves—suddenly we weren't just a good Canadian company; we were part of the international ballet conversation."

Nureyev's presence also inspired a wave of Russian ballet teachers to settle in Toronto. Former Kirov dancers like Marina Sorokina and Alexander Dunin established studios throughout the city, bringing authentic Vaganova method training to young Torontonians. These schools incorporated distinctly Russian elements: rigorous daily classes, emphasis on proper placement before flashy tricks, and the incorporation of character dance from Russian folk traditions.

The Post-Soviet Wave: New Traditions in a New Home

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 catalyzed another significant migration of Russian dance talent to Toronto. Facing economic uncertainty at home, numerous dancers, choreographers, and teachers sought opportunities abroad. Toronto, with its established Russian community and growing reputation as a ballet center, became a natural destination.

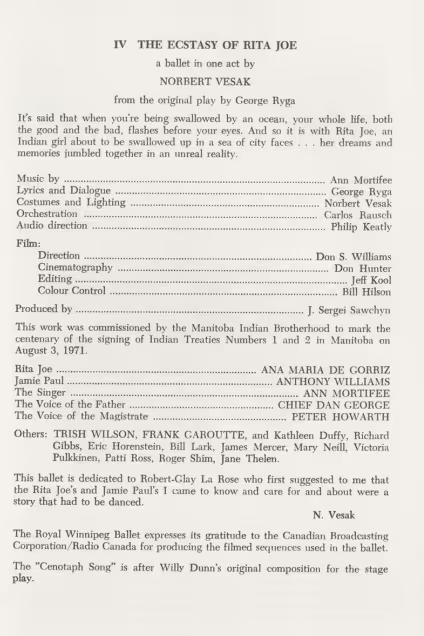

The Karpov Ballet Academy, founded in 1994 by former Bolshoi soloists Andrei and Elena Karpov, exemplifies this era. Operating from a converted Victorian home in Roncesvalles, the school combined traditional Russian training with contemporary sensibilities. Their annual "Nutcracker" production became a neighborhood tradition, featuring local children alongside professional Russian-trained dancers.

"We brought our Russian souls but adapted to Canadian realities," Elena Karpov explained in a 2005 interview. "In Russia, we selected only children with perfect bodies and flexibility. Here, we teach anyone with passion. It's more democratic but still demanding."

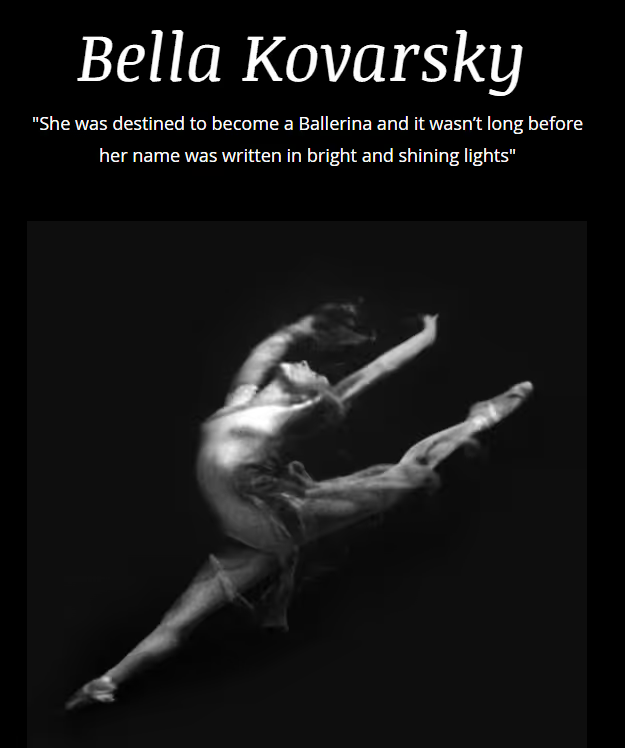

Another renowned school - Bella Kovarsky's Ballet School - was celebrated as one of Toronto's most respected classical dance academies, known particularly for its rigorous Vaganova method training. Bella had the privilege of instructing esteemed Ballet luminaries: Mikhail Baryshnikov and Alexander Godunov. It was in the year 1982 that Bella, armed with her profound experience and expertise, fearlessly forged ahead to establish the Bayview School of Ballet in the city of Toronto. In a momentous endeavour, Bella's pioneering efforts introduced the venerable Russian classical teaching method to the Canadian landscape, thereby enriching the tapestry of Canadian culture.

This post-Soviet influx enriched Toronto's ballet diversity. While the National Ballet maintained its mixed English-Russian-Danish stylistic heritage, smaller companies embraced more distinctly Russian identities. The Toronto Festival Ballet, founded by Moscow-trained Aleksandr Antonijevic in 1998, specialized in Russian classical repertoire seldom performed by larger companies, from "La Bayadère" to "The Fountain of Bakhchisarai."

Contemporary Relevance: From Ryerson to Revolution

Today's Toronto ballet landscape reveals Russian influence at every level, from recreational dance schools in suburban strip malls to elite training programs. The School of Toronto Dance Theatre and Ryerson University's dance program both incorporate elements of Russian pedagogical methodology, particularly in their technical training components.

Professional companies throughout the Greater Toronto Area employ numerous Russian-trained dancers, teachers, and artistic directors. Modern Toronto has also seen interesting fusions of Russian ballet traditions with contemporary Canadian sensibilities. Choreographer Vyacheslav Osotov's 2019 work "Immigrant Dreams," performed by the Toronto Dance Collective, used classical Russian ballet vocabulary to explore themes of migration and cultural identity. Its premiere at Harbourfront Centre featured dancers from fifteen different national backgrounds performing distinctly Russian choreographic forms—a perfect metaphor for Toronto's multicultural ballet community.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Cultural Exchange

The story of Russian ballet in Toronto is not merely about the preservation of tradition but about dynamic cultural exchange. What began with a handful of émigré dancers has evolved into a rich ecosystem where Russian technical excellence merges with Canadian creativity and openness.

From Boris Volkoff's pioneering efforts to today's diverse dance landscape, Russian ballet has both transformed and been transformed by Toronto. The exchange continues with each plié and pirouette, each carefully passed-down combination, each performance that bridges old world and new. In studios across the city, as piano music accompanies dancers at barres, the distinctive Russian ballet lineage lives on—transformed by its Toronto home but never forgetting its roots in the theaters of Moscow and St. Petersburg.

If you enjoyed reading this article, you may explore more insights and resources on ballet training, ballet news, and ballet history on our blog.